History

The Roxburghe Club is the oldest and most distinguished society devoted to printing unpublished documents and reprinting rare printed texts, among them unknown or neglected works of English literature and history. The list of publications now runs to almost three hundred volumes that range from medieval manuscripts in facsimile and important works in Early and Middle English, to more modern texts, unpublished Jacobite documents, the correspondence of Garrick and the Countess Spencer, and Disraeli’s letters.

The Club’s books are outstanding examples of fine printing – the reproductions are often by new and innovative techniques. The combination of important texts with distinguished typography has, from the beginning, commended Roxburghe books to libraries and connoisseurs alike.

Back to topThe Club

The Club came into existence on 16 June 1812 when a group of book-collectors and bibliophiles, inspired by the Revd Thomas Dibdin, panegyrist of Lord Spencer, the greatest collector of the age, dined together on the eve of the sale of John, Duke of Roxburghe’s library, which took place on the following day. This was the greatest private library of the previous age, and the sale was confidently expected to break all records, and it did. The first edition of Boccaccio (then believed to be unique) printed in 1471 made £2,260, a record that stood for more than sixty years, and the Duke’s Caxtons made equally high prices. The diners decided that this occasion should not be forgotten and so they dined again together the next year on June 17, the anniversary of the sale, and again the year after. So the Roxburghe Club was born and its members still dine together each year on, or about, that memorable day.

Back to topMembers

The original members were all friends and were drawn from the ranks of the nobility, the professional and academic classes, but it was books that levelled the barriers that might otherwise have existed then between them. Over two centuries later, this mixture has continued unchanged. The owners of the surviving hereditary libraries of Britain (fewer than there were in 1812) have been joined by those who have built great collections since, by writers and judges, civil servants, soldiers and explorers, as well as librarians, palaeographers and other scholars, all linked by their love of books. The complete list of members since the foundation of the Club can be found under ‘Membership since 1812’ on this website.

Back to top‘Black-letter’ books

The earliest Roxburghe books were all reprints of 15th or 16th century pamphlets, usually in verse, all rare, sometimes the only copies known. This taste for ‘rescuing’ little books like these had been growing throughout the 18th century, along with new scholarly interest in Shakespeare and his contemporaries. The early members of the Club gave these reprints to each other. As the Club grew, the annual subscription was put towards the publication of the ‘Club books’, published collectively by the Club, as distinct from ‘Members’ books’, those that members produced to present to each other.

Back to topMedieval texts

From 1827, when George Watson Taylor printed the English poems of Charles, Duke of Orleans from Harleian MS. 682, the Club also began to print unpublished medieval texts, pioneering scholarship in this field. The great palaeographer Sir Frederic Madden was employed by the Club to provide scholarly editions of important Old English texts, among them Havelok the Dane (1828), William and the Werwolf (1832) and Gesta Romanorum (1838). The first texts of The Owl and the Nightingale (1838) and The Ayenbite of Inwit (1855) followed. Important historical texts included Manners and Household Expenses of England in the XIIIth and XIVth Centuries (1841) and Letters and Dispatches of Sir Henry Wotton (1850). Between 1861 and 1867 F. J. Furnivall edited several important texts, before he himself set up the Early English Text Society which then took over this kind of publication.

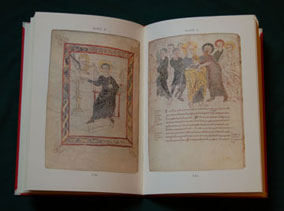

Back to topFacsimiles

Several of the Club’s early books contained facsimiles, and in 1873 the Club experimented with almost all the extant methods of reproduction when reprinting five early tracts from Samuel Pepys’s library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. This was followed by Henry Coxe’s edition of The Apocalypse of St John the Divine (1876), from a manuscript in the Bodleian Library, complete and in colour, the first medieval manuscript to be thus reproduced. Another landmark came with Les Miracles de Nostre Dame (1885), the first illuminated manuscript to be reproduced by photolithography. This tradition, continued by William Griggs and Sir Emery Walker, underlay the work of Sir George Warner and M. R. James, whose texts, accompanying reproductions of superb quality, laid the foundations of modern scholarship in the field of medieval manuscripts in the first half of the 20th century. Among important later texts published by the Club was A Transcript of the Registers of the Worshipful Company of Stationers from 1640 to 1708, in three volumes (1913-15)

Back to top‘Roxburghe-style’ binding

From the outset, Roxburghe books have been bound in a particular style, quarter leather with plain sides. For the first little books, plain black or brown calf and maroon paper sides sufficed. As the books grew more substantial, morocco backs and buckram sides were substituted, designed with considerable elegance. These are the ‘Roxburghe-style’ bindings that private presses and others have imitated. Apart from the binding, the Club has always taken great interest in the typographic appearance of its books, many of them among the most notable examples of letter-press printing. C. H. St John Hornby, founder of the Ashendene Press, was long a member, and the standards that he set have been reflected in all the books published by the Club since.

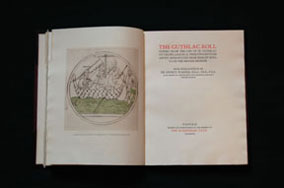

Back to topThe Roxburghe Club’s more recent publications

The Club’s publications over the last hundred years have offered an astonishing diversity of subject matter, from the autobiography of Lady Anne Clifford to Byron’s annotated copy of English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, from a facsimile of the 7th-century Stonyhurst Gospel to Rumpel-Stiltskin, a jeu d’esprit by the young Disraeli, from Cock Lorell’s Boat, a little verse pamphlet of 1518 of which no complete copy is known, to the great folio Jan Huygen van Linschoten and the Moral Map of Asia, printed in England in 1598, the definitive account of the Portuguese discoveries…

Among the latest books to appear are The Library of Thomas Tresham and Thomas Brudenell by Nicolas Barker and David Quentin, a reconstruction of the greatest Recusant library in England from the still extant books and original documents, and Inigo Jones’s Roman Sketchbook, a facsimile of the little notebook bound in limp vellum that Inigo Jones took with him on his first epoch-making visit to Rome with the Earl of Arundel in 1612-14 and continued to use later. This is accompanied by a companion volume by Edward Chaney tracing exhaustively the sources from which Jones drew the pictures and texts with which he filled his notebook’s pages.